Is Your Team A Safe Place?

The Scene. A recent team offsite of a coaching client. The facilitator is skillfully working the leadership team through the findings of a team effectiveness assessment. She eases the team into a guided reflection on their practices around trust and managing conflict. As various team members weigh in on their experiences within the team, she reinforces the openness being exhibited and gently probes for more.

The Scene. A recent team offsite of a coaching client. The facilitator is skillfully working the leadership team through the findings of a team effectiveness assessment. She eases the team into a guided reflection on their practices around trust and managing conflict. As various team members weigh in on their experiences within the team, she reinforces the openness being exhibited and gently probes for more.

Then that moment arrives – another random encounter with a blog-worthy topic.

As the facilitator weaves the thread of meaning in and out of the team members’ offerings, she pauses for a moment. “Here’s a question,” she muses aloud. “Is this team your safe place?”

Silence falls among the team members – one of those deep, pure silences you hope for as a facilitator of team process. One of those silences that challenges whomever breaks it to speak truth.

Enrichment. I don’t often get the opportunity to be an observer of other team facilitators’ work, so my presence in that room was a real pleasure. As a consultant for team development myself, I paid close attention to both my client and the facilitator’s impact on the process. (I’m grateful to both of them for their permission to discuss this event in this article.)

Here’s one aspect of the facilitator’s work that grabbed my attention and held it: in asking that question, she introduced a standard, a mental model, for the participants to try on: namely, that their team should be a safe place. This particular team grabbed onto the mental model and ran with it in a very productive fashion. Her choice to use it enriched their process.

Spreading the Wealth. Her choice to use it also enriched my process. I’ve spent hours since then puzzling over the generalizability of that mental model. I keep turning the following proposition over and over in my mind:

Does “effective team” = “safe place”?

And now I offer it to you: Is your team, the one you lead or the one you belong to, a safe place? Do you feel it is important for it to be?

Before you or I answer our question, this inquiry seems to need some grounding in relevant literature. Let’s go take a look, shall we?

Defining the Currency. The construct of team psychological safety, which is what we are talking about here, borrows from the thinking of psychologist Edgar Schein and affiliated others that dates back to the 1960’s. Schein’s contributions to the study of human systems are numerous so I won’t attempt to summarize them here. One relevant contribution emanated from his deep interest in change – most notably, in how change occurs as an interaction between individual psychological forces and human/organizational system dynamics.

In one article that serves as an overview of his 50 years of research in human systems, he describes change as “intrinsically difficult and somewhat painful” due to the way it inherently requires upsetting some sort of “quasi-stationary equilibrium” that we’ve established in the current state. Motivation to change does not arise, then, until individuals feel “secure enough” to accept the signals that change is needed. That security, he further posits, is dependent upon the individual feeling “psychologically safe” in the human system so that “he or she can accept a new attitude or value without complete loss of self.”

Heady stuff. Put more simply, Schein is saying that human beings, alone and together, have a marked tendency to perpetuate their current ways of being and doing things. Even when those ways aren’t working optimally for us, we tend to maintain status quo and resist change or new learning. We get comfortable and settle in, even if the chair is a little too hard or too soft. Breaking out of this “quasi-stationary equilibrium” (what a great phrase!) requires both information that alerts us to the need to change AND that we feel safe enough from threats to our self-identity/esteem that we can risk trying to make the change. Then, like Goldilocks, we go in search of the chair that feels “just right.”

What kind of threats to our self-identity are important enough to qualify as “psychologically unsafe” and therefore as reasons our team may not feel like our safe place?

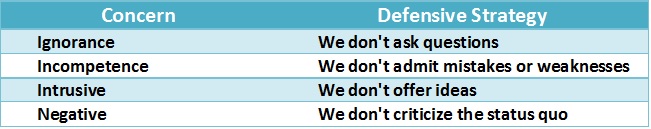

Paid Back with Interest. Amy Edmondson of Harvard Business School provides valuable insight on this additional inquiry. In a terrific TED talk, she defines team psychological safety as a “belief that it’s absolutely okay (in fact, it’s expected) to speak up with concerns, questions, ideas or mistakes.” She then goes on to catalogue the major threats to team psychological safety as the following: concerns with coming across as either ignorant, incompetent, intrusive or negative. Each concern leads to a distinctive defensive strategy:

When we feel less than psychologically safe in our team, we default into well-learned practices of impression management. We act “as if”: as if we know what we’re doing at all times, as if we possess whatever knowledge is needed, as if we’ve added all thoughts we have on a matter and as if the way things are going is just fine with us. We withhold our truth. To do otherwise, we fear, would threaten our belonging and status in the team.

Safety versus Trust. I expect that some of you who have read this far are now wondering: “Well, hmmm, this is kind of interesting stuff. But isn’t this just another article about the importance of trust in teams?” I asked that question, too, as I formulated this blog.

Is there a difference between safety and trust in teams? Was it meaningful that the facilitator in the opening scene asked the team members if the team was their “safe place,” not their “trust place”?

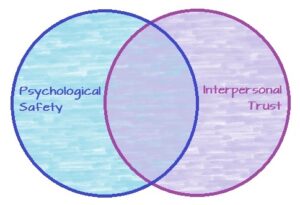

Turns out it was. While the two constructs share some conceptual space, a Venn diagram of “trust” and “safety” in teams would show some degree of unique space on either side of the shared space. Back to Amy Edmondson one more time: she, among others, distinguishes team psychological safety from interpersonal trust (visit that book chapter here). The former, as referenced earlier, may be defined as “a shared belief held by members of a team that the team is safe for interpersonal risk taking.” Interpersonal trust, in contrast, may be defined as “the expectation that others’ future actions will be favorable to one’s interests.”

The shared space in our Venn diagram? Both concepts involve internalized evaluations of vulnerability. In addition, they each evoke decision-making regarding how to minimize the potential consequences of that vulnerability. Last, both psychological safety and interpersonal trust, when present, contribute to the possibility of team effectiveness.

The unique space? According to some of the research in this arena, team psychological safety operates in a more immediate timeframe, as a moment-by-moment calculation of the risk of speaking out, of asking a question, of making a mistake, etc. Trust, in contrast, describes more of a long-term consideration based on assessments of others’ trustworthiness. Secondly, team psychological safety is thought to be reflective of what the team gives to the individual (e.g. “do I feel safe speaking up about our product quality or will I be branded a ‘troublemaker’?”) while interpersonal trust is thought to be something that the individual gives to others (e.g. “I know and trust Mike so I’ll give him the benefit of the doubt here.”)

This part of the exploration may feel a little dense about now, so here’s a simple way of describing the difference: while I may trust many of my teammates based on a series of interactions with them over time, I still may not feel safe about speaking up on a sensitive issue or asking a question I’m afraid may come across as uninformed, too negative or pushy. I bet if you sit with that distinction for a few minutes and play it out against situations in your own work life, you’ll find its relevance. I know I did.

Is Safety a Gold Standard for Team Efficacy? So if team psychological safety isn’t the same as trust, should it join trust as an additional sine qua non of team effectiveness? Intriguingly, some qualifying conditions exist, based on some of the research on this topic…and on personal preferences.

While I suspect many of us would prefer to work on teams that have higher psychological safety, I am reminded of a scene from much earlier in my career. The team I belonged to completed a team building session in which we were asked to describe what we wanted our experience in the team to look like. When my turn came, all of my youthful zeal rushed forth in a stream of ambitious attributes: “I want to work in a team where we challenge each other to constantly get better, where we can say anything to each other without fear of looking stupid, and where we are safe to truly be our full selves at work every day.” A respected older male colleague of mine looked at me and said, carefully, “Deb, some of us don’t look to get those kinds of things from the people we work with. I mean, I’m all for having a friendly and supportive work place. But you’re describing the kinds of relationships I have in my personal life.”

Backing up my former colleague’s view of the issue, several studies suggest that psychological safety isn’t necessarily the gold standard for every team. It doesn’t guarantee team effectiveness, in and of itself. Its effect on team efficacy is moderated by two additional variables: whether uncertainty is present and interdependency is important to success.

The Silver Standard? While psychological safety may not be the gold standard for every team, the more teams have to navigate together through conditions of uncertainty, the more important it becomes. Why is that? Because those conditions are characterized by a higher need for learning and change. And, back to Edgar Schein, most of us are status quo-loving machines who are not naturally eager for change and new learning, despite our protests to the contrary.

Also, we can’t just disappear into our offices or behind our laptops and work this kind of change out on our own. We have to figure it out with others…which makes it messier, less predictable and more rife with those pesky interpersonal dynamics. In conditions like that, psychological safety is worth its weight in…silver.

Netting Out the Value. So back to the opening scene. What’s the value of being able to answer that facilitator’s question with: “Yes, my team is a safe place. I feel I can speak up on issues outside my direct statement of work without fear of looking ridiculous. I feel I can admit to mistakes without being ostracized. I feel I can ask tough questions and be taken seriously”?

If you’re in a team that needs to learn together, to try novel solutions, to explore various ways of solving problems in an uncertain environment, turns out an affirmative answer is pretty darn valuable.

For the rest of us, perhaps we should strive to build teams that are at least “safe-ish.”

Given the increasing complexity of the challenges our human systems face every day, a commitment to building some measure of team psychological safety with each other seems like a wise investment. What’s the opportunity cost if we don’t? Borrowing from Amy Edmondson one last time: “Every time we withhold, we rob ourselves and our colleagues of small moments of learning…and we don’t innovate, we don’t come up with new ideas…we are so busy managing impressions, that we don’t contribute to creating a better organization.”

Change is stymied or superficial; transformation doesn’t occur. The “same old” stays the same old. And Goldilocks never gets up from her slightly uncomfortable seat to find the one that fits just right.