The Scene. A two- day gathering of senior managers of a business unit. The key decision to be made: whether to close one of several facilities, resulting in job loss for a number of affected individuals.

The Scene. A two- day gathering of senior managers of a business unit. The key decision to be made: whether to close one of several facilities, resulting in job loss for a number of affected individuals.

Preparation for this decision had been going on for months – data gathered, various scenarios mapped out, and analyses run. The leader had framed the meeting as “The Summit” at which a consensus decision would be reached, no matter how much time it took to get there.

As the session began, the leader reinforced the meeting purpose. A facilitator took over, carefully walking through the ground rules and agenda. The twelve participants listened attentively and clarified the decision-making process: the data would be shared, dissected and discussed. Then each person would be expected to contribute his or her perspective, with the leader weighing in last. The stage was set.

Act One. Several team members tasked with assessing the various financial, operational and human resources implications of a “keep it open” versus a “close it” outcome took the floor. Hours of intensive data review and discussion unfolded. Key questions and salient points populated an increasing number of flipcharts around the room. Decision factors were identified. Team members made inquiries, debated alternatives, and scribbled furiously on their notepads.

Breaks were taken. Day one ended with adjournment and a second day of discussion began…but the intensity in the room never wavered.

At one point early on the second day, a blind poll was taken to gauge the need for continued discussion. A time-out was taken while team members considered all they had heard. The outcome would impact hundreds of employees’ lives as well as their own, after all, and for some of these leaders, it was the most significant leadership decision they had ever been asked to make.

Act Two. After the brief respite, the team members returned to the room and registered their opinions on slips of paper. The facilitator sorted them through as the team waited anxiously. The outcome of the blind poll: roughly a third of the team favored closure, another third favored staying open with various turnaround measures put in place, and the remaining third was still undecided. The team paused to reflect on the split outcome, acknowledged it as a reflection of the difficulty of the decision, and then got back to work.

After several more hours, the business leader signaled the facilitator that the time had come to test the waters again for agreement. This time, he asked each team member to openly express his or her point of view on the options (“keep it open” or “close it”) along with a rationale. The facilitator wisely advised the team members to each write down their answer before the sharing began so as to guard against the potential influence of group think as the tally mounted. The air in the room was charged with tension as team members silently recorded their perspectives.

It was time to lay their cards on the table.

Final Act. The first team member took the floor, followed by the person seated next to him, and so on. A startling scene unfolded.

Calls to close the site were repeated, one after another, with detailed rationales provided. Several team members noted they found the outcome emotionally difficult yet they also felt it was the right business decision. No one abstained from voting. No one wavered.

By the end, every single team member had agreed that the best option was to close the site. A few even noted that doing so meant they would lose their own jobs.

Then the team leader took the floor.

“Et tu, Brute?” He slowly looked around the room, scanning the participating leaders’ faces. They sat quietly, expectantly awaiting his commentary.

“I’m disappointed in every one of you,” he began. “I think you took the easy way out rather than making the tougher decision, which is to keep it open and then figure out how to make that work. I expect more of you as leaders. ”

He then said, “We are keeping this site open.”

Dramatic Pause. How do you envision the scene playing out from there?

I happen to know because I was in that room. After a short period of stunned silence, first one team member and then the next began hedging against the positions they had taken. “I wasn’t as definitive as I may have sounded…” or “Well, I’d be fine with that, too…” Others jumped right to implementation and began offering ideas on how to execute against the team leader’s decision to keep the site open. Some just sat quietly.

The meeting moved on from there. No one addressed the impact of the leader’s words or actions.

The Glass Menagerie. This article picks up where my last article left off; namely, how to create – or in the case of the above case study – destroy team psychological safety. As discussed in the prior article, team psychological safety can be defined as “the belief that it’s absolutely okay (in fact, it’s expected) to speak up with concerns, questions, ideas or mistakes.” This kind of safety proves to be critical to team performance when a) team members must work together for success and b) meaningful learning and problem solving must occur within that interdependent context.

In teams with higher psychological safety, the focus is not on safety just to maintain comfort; the focus is on productive discussion and interpersonal process in pursuit of a shared goal. Differences of opinion get aired, consequences of team decisions are explored, team members reflect on the impact of their behaviors on each other, and needed adjustments are discussed within the team (rather than outside of it, which often happens in teams with lower psychological safety).

So how does psychological safety get built (or destroyed) in teams? Turns out the leader has a lot to do with it.

The Lead Actor. While team members certainly contribute to team psychological safety and the value it can bring, research in this area suggests that the team leader’s behaviors are particularly impactful. My experience suggests the same. Given that team psychological safety has a lot to do with our calculations of interpersonal risk versus gain, the leader (gatekeeper to many tangible and intangible symbols of our interpersonal standing) can greatly influence our willingness to take those risks.

Accordingly, several leader practices help to determine a team’s psychological safety – and ultimately, a team’s effectiveness in the kind of high stakes decision-making situation the case study describes.

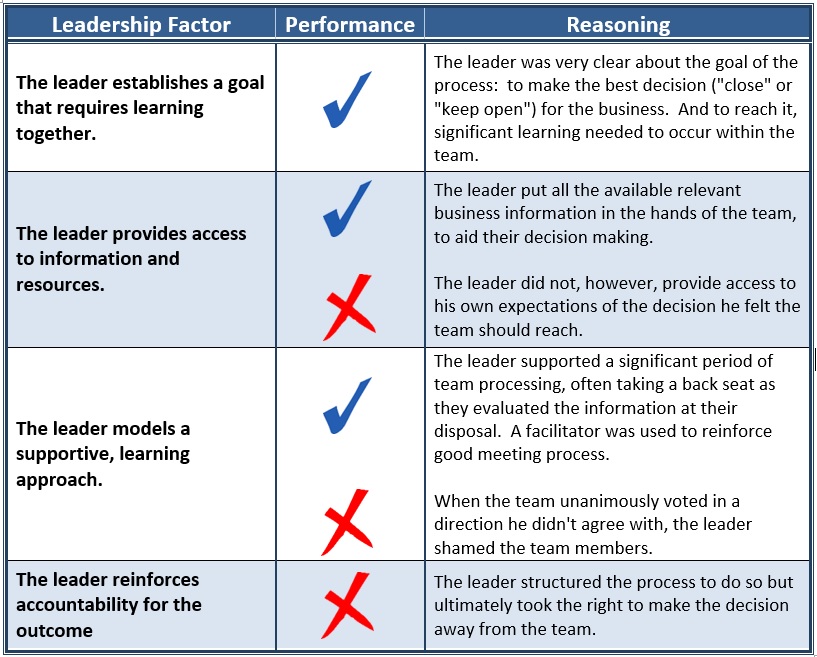

- The leader establishes a goal that requires learning together: Learning together requires interpersonal risk. Good leaders establish a clear, compelling goal that necessitates change and growth so that learning will occur. They also engage in “double loop learning” in ways that build the team’s ability to stand back from its own process, examine beliefs & assumptions, and reflect on how to do better together.

- The leader provides access to information and resources: Leaders are uniquely positioned to provide “context support” – access to needed information and resources to enable better, more efficient learning and decision making. The better the information team members have to work with, the better their ability to support a position they are taking, heightening the sense of safety in taking it. I’m sure we’ve all worked with leaders who, instead of openly sharing information or access to resources we needed, doled one or both out in a controlling fashion. The effect on the team is rarely positive.

- The leader models a supportive learning approach: A team is more likely to seem a “safe place” if the leader models good learning behaviors herself, is non-punitive when mistakes are made or questions are asked, and provides coaching and support when needed. Leaders like this encourage open discussion and exploration of the content, reducing tacit pressure to not speak up or to maintain the status quo. They also demonstrate a comfort with their own uncertainty and “learner status” at times, modeling constructive vulnerability for team members.

- The leader reinforces accountability for the outcome: It is possible to have too much psychological safety, however. Re-introducing the metaphor used in my prior article, Goldilocks can simply fall asleep in the softest bed represented by having an overly supportive, “fail safe” environment. Leaders need to manage the tension between establishing conditions of psychological safety and holding team members accountable for doing the hard work required to reach the goal. They need to find the leadership position that is “just right,” combining high safety with high accountability (see Amy Edmondson’s TED talk for more on this).

The Critic’s Review. So what went wrong in the leadership team scenario I presented at the beginning of this article?

Let’s run a quick scan across the four leader factors:

From my perspective, the stated goals and structure of the decision-making process aligned fairly well with principles of team psychological safety. And the leader supported significant learning within his team as the first day and a half unfolded.

Closing the Curtain. So why did this particular leader take the dramatic turn into shaming his team and pulling back the decision he’d committed to making in a consensus model? He set out with good intentions around sponsoring a decision-making process that would both benefit from the best thinking of his leadership team members as well as lead to better adoption afterward given their participation in it. How did he end up acting as a dangerous leader?

My hypothesis is he hadn’t done his own deep, reflective work to assess the outcome he truly wanted. Believing either outcome to be a viable alternative as long as the team’s work with the data supported it, he designed a consensus-based decision making process he ultimately couldn’t support.

Ironically, the team members’ thorough processing and attempt to reach consensus did have a learning benefit, albeit an unintended one. Their work catapulted the leader to a deeper awareness of his own underlying beliefs around what “good leaders” should decide, which to him meant keep the site open.

Unfortunately, in messaging that to his team members in the way that he did, he had a destructive effect on the process and likely on the long-term health of that team, at least under his leadership. Another valuable reminder that the most important acts of leadership, both small and large, require ongoing self reflection and awareness. Without it, even the most well-intended leader can become dangerous.